The idea of this project comes from an exciting scientific expedition to the Prince Edward’s sub-Antarctic archipelago in 2018.

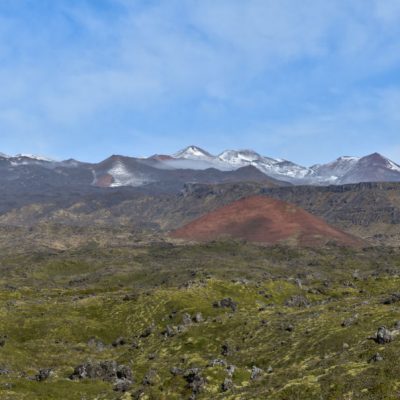

After eight days of sailing in the South African icebreaker Agulhas II, we crossed Atlantic, Indian and Antarctic waters, and arrived at Marion Island to stay one month in its research station. This archipelago stands out as one of the most remote and inaccessible places in the world, conserving the last pristine and undisturbed areas of the planet.

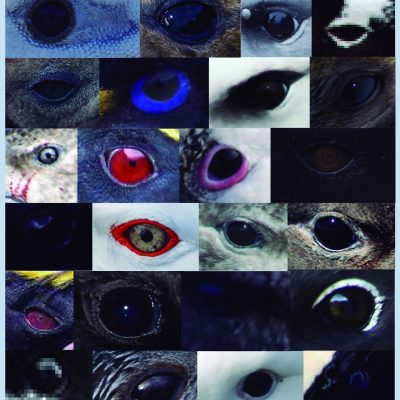

Here, stand out both the endemic flora and the impressive colonies of mammals and seabirds, and despite its small area, these islands provide the largest breeding areas for seabirds (pelagics) in the world! Wandering around are the famous albatrosses, of which we were lucky to enjoy up to 7 species: among them the mythical wandering albatross —largest flying bird on the planet, with up to 3.7 meters of wingspan—. In addition to large poulations of penguins, elephant seals, shearwaters, petrels, cormorants, seals, terns, diving-petrels, storm-petrels, Killer whales!

The high density of seabirds is so important in these islands, that their presence has become essential to regulate the ecosystem. Birds produce an enormous amount of organic matter (guano, urine, carcasses), which provides the necessary conditions for soil development and plant growth. This vegetation, in turn, forms the necessary habitat for the colonies of seabirds and marine mammals. Because of this, these ecosystems are very vulnerable, since significant changes in bird densities might produce multiple cascading effects at different trophic levels.

The negative note is that, this exceptional biodiversity is in serious danger, in particular due to the impact of invasive species (aggravated by climate change), and especially by the introduction of cats and mice, which have reduced bird densities by more than 90%. For example, in Marion Island, cats were killing more than 630,000 petrels annually, and even extinguished one of them (Pelecanoides urinatrix). Although cats have already been eradicated, more worrying are the rodents, that have learned to prey on the albatross chicks, which devour alive in their nests. In fact, we suspect that this impact on birds has affected the flows of nutrients and has caused the decline of herbaceous grasslands, that supported the animal colonies.

Our aim will be to study, if the introduction of invasive species have caused multi-trophic cascades in response to invasive species in the sub-Antarctic —quickly extinguishing these communities— as well as the possible recovery after the disappearance of the invaders. We hope that these results will inspire more private and governmental initiatives to prioritize the eradication of invasive species, with the intention of saving millions of seabirds and protecting the last pristine habitats of the planet.